HPRC 2022-23

As Payload Division Lead during the 2022–23 academic year, I led an ever-growing team of around 40 peers to develop an innovative payload for the team’s launch vehicle. As with the previous year, the Spaceport America Cup competition did not provide much guidance in terms of functional payloads, but we did have the benefit of competiting in the previous year’s competition and the knowledge that we gained from that.

At the start of the year, the Payload Division gathered to reflect on the previous year’s payload and its performance and come up with new ideas for the current year’s payload. Through this round of brainstorming, the team arrived at a mission concept that highlighted both the competition’s preference for scientifically significant payloads, as well as WPI’s heritage with robotic paylods: autonomous deployment of remote weather-station units throughout the landing area. The team also came up with multiple vehicle concepts to complete the mission.

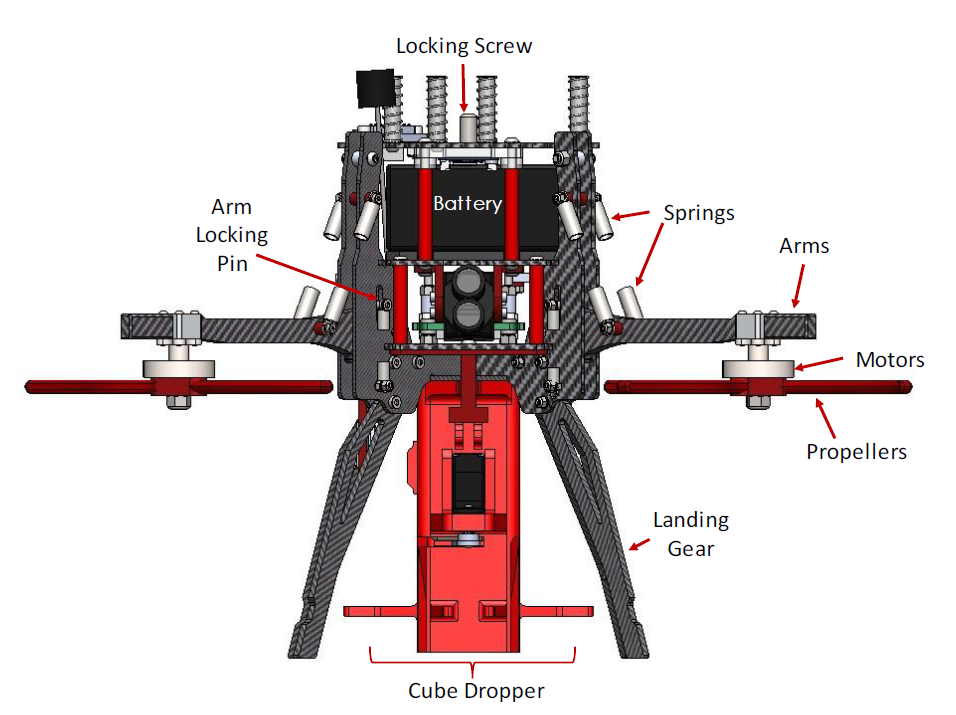

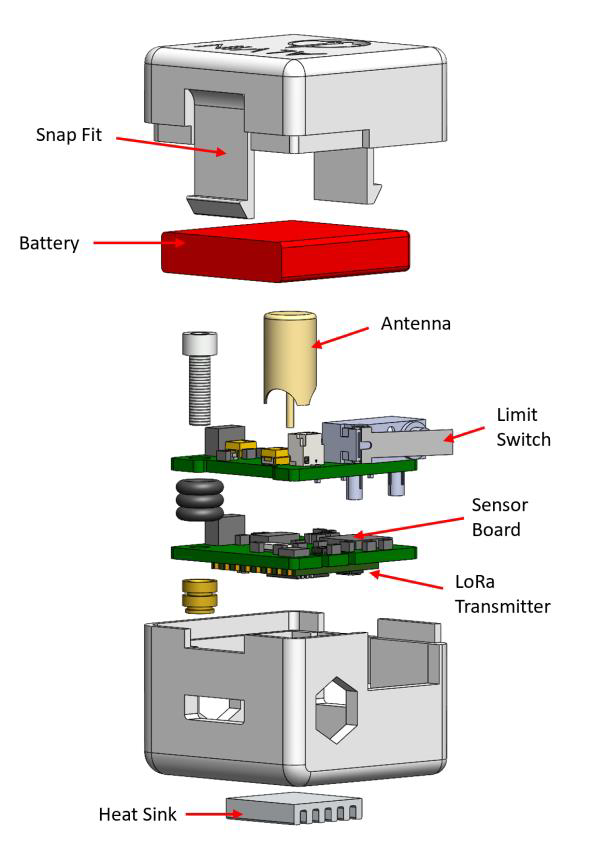

Prototypes of these concepts were developed, and in the end, we decided on developing an autonomously deployed folding-arm quadcopter that would deploy weather-stations in the form of small cube-shaped sensor packages. The entire quadcopter vehicle, along with its robotic retention and deployment system were constrained to fitting within an integer number of CubeSat “units” (10x10x10cm), providing an interesting engineering challenge.

Similarly space-constrained were the weather-station cubes, albeit on a much smaller scale—three of these cubes needed to fit within a deployment system under the quadcopter. The cubes and their deployment systems were developed, mechanically, in conjunction with the team’s Electronics and Programming Division, who developed the electrical systems that fit inside the cubes and provided them functionality.

Due to the team’s ambitious plan of deploying the quadcopter mid-air, from the rocket descending under parachute, we developed a much larger hexacopter capable of carrying the entire payload truscture to complete flight-like drop tests and missions. However, during initial testing of the hexacopter, we encountered stability and oscillation issues that we were unable to resolve in time prior to competition. Since we were unable to complete the test campaigns we set out to at the beginning of the year, we resulted to doing smaller-scale system-level tests, such as testing the quadcopter mission and software separately by launching it from the ground instead of dropping it from the air.

In June 2023, I travelled with the team to the Spaceport America Cup in New Mexico. There, we had the opportunity to showcase our years’ work to the other teams as well as to the judges. This competition would also allow us to show our recovery from last year’s in-flight failure along with our heightened focus on safety and reliability. After passing safety inspection and completing final integration tasks, we loaded the rocket on the launchpad and armed it for launch. Upon launch, the vehicle ascended to an apogee of just over 10,000 ft where it deployed its drogue parachute, unfortunately pulling the main parachute out with it as well. Although the payload was developed to deploy from the descending rocket, that functionality was disabled to comply with new last-minute regulations imposed at the competition. Upon recovery of the rocket and payload, the cubes were tested with manual deployment and weather data was collected at the landing site. This demonstration of the payload’s functionality, along with the overall design and construction, led to the team placing 3rd in the competition’s SDL Payload Challenge.

The final report found below and further info can be found on the team’s website.

08/2022 – 07/2023